The UK Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act in 7 Minutes

November 10th, 2023

A 7-minute read

Gaps in financial crime legislation and controls have created opportunities for criminals to hide in the void between organisations and behind corporate entities and opaque digital identities. How can we address these weaknesses?

The UK Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 might be the answer and revolutionise the way we fight financial crime. This groundbreaking act is intended to:

- Strengthen data sharing between the public and private sectors

- Create stricter regulations on company registration

- Reform limited partnerships to create a more robust defense against criminal activity

- Create a new offence of failure to prevent fraud

What do financial crime and compliance professionals need to understand about this act? Read on to find out.

UK Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act Background

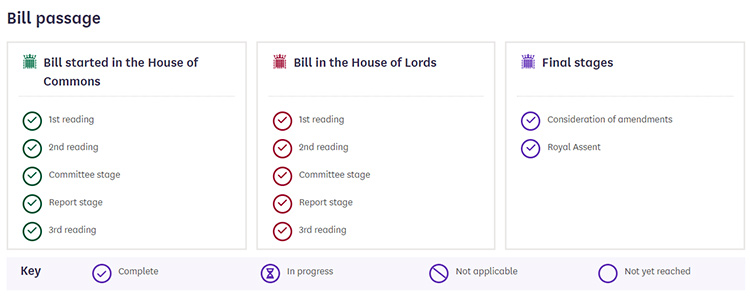

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill was first introduced in the UK House of Commons on 22 September 2022. It comes hot on the heels of the Economic Crime Act of 2022, which introduced wide sweeping reforms of ultimate beneficial ownerships (UBO) identification for high-value properties owned by corporate entities.

Source: Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 – Parliamentary Bills – UK Parliament

The new bill passed through both UK parliamentary bodies, the House of Commons and the House of Lords, where amendments were recommended. These amendments were reviewed and considered in the Commons, where a final review was made by the Lords before the bill was submitted for Royal Assent. On the 26 October 2023, the bill received Royal Assent to become law, and it’s now known as the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023.

As the latest in a raft of game-changing legislation, this act will hopefully make it harder for criminals to succeed and finally give the good guys some teeth to help fight financial crime.

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill Key Areas

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act will impact four key areas—information sharing, company registration, limited partnership reform and enhancements to fraud offences. These focus areas will result in greater information sharing at financial institutions (FIs), higher-quality corporate registry information that can be used during onboarding and for perpetual KYC (pKYC), and the need for greater monitoring of limited partnerships. On the fraud side this legislation will create a new offence of failure to prevent fraud for corporates.

Information Sharing

The main emphasis of the act is on enhanced private-to-private and private-to-public information sharing.

Currently, data sharing is limited because the existing legislation is voluntary and lacks firm guidance. Current information sharing gateways are open for interpretation and can be interpreted differently by various legal teams. This often results in limited, or no, information being shared between relevant parties because legal teams will err on the side of caution.

The legislation now changes this by providing clearer gateways and stronger legislation to enable better private-private and public-private information sharing, for the purpose of preventing, investigating and detecting financial crime.

In essence, the legislation grants legal immunity from civil liability when sharing information pertaining to suspected financial crime. Law enforcement is now permitted to proactively gather intelligence from FIs on suspected illegal activity without needing a pre-existing Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) from the organisation.

There are two parts to this legislation, direct and indirect sharing of information:

Direct sharing

This is sharing between two regulated businesses, such as two FIs. In this case, a suspicious transaction has been made between the organisations, and they want to collaborate to investigate the activity.

Indirect sharing

This is a much more interesting development. It allows organisations to share information for the purpose of preventing, investigating and detecting financial crime via a third-party intermediary. Organisations can include FIs, crypto asset exchanges and custodian wallet providers, large tax advisors, law firms, accountancy firms, auditors and insolvency practitioners. Indirect sharing allows these organisations to share customer information that relates to financial crime with an intermediary. Previously, a customer might have information but not know what to do with it. Once established, this type of sharing will work in much the same way as CIFAS in the UK, where registered organisations can upload relevant information pertaining to a subject and potential financial crime. An example is when an FI offboards a customer due to suspicion of engagement in financial crime and other organisations. They can access this data when onboarding the same customer to make an informed risk decision.

How this looks in practice, and what organisations can act as the intermediary, is still to be determined. However, access to this information could be game changing when fighting financial criminals. The only challenge I can foresee is information validation: the customer information that’s uploaded must be validated to ensure innocent parties are not detrimentally affected by being wrongly tagged as potentially linked to financial crime.

What does this mean for financial crime and compliance programs?

The act sees the largest reform of Companies House, the official Registrar of UK businesses, and the UK company incorporation process since its inception in 1844. Under the new rules, companies must verify the identity of all new and existing directors, people with significant control, and those delivering documents, resulting in more accurate and up-to-date information on the company registry.

Companies House, under the new legislation, will now have the authority to check registrations, challenge discrepancies and reject information submitted to or already on the company’s register. As a result, Companies House becomes an active gatekeeper. They can identify if there is suspicion of criminal activity and act accordingly, such as when a company:

- Provides insufficient or conflicting information

- Fails to sufficiently answers questions raised during registration

- Doesn’t provide adequate answers to questions about existing registration information

This change will be the first of its kind globally. It seeks to deter criminals who try to use opaque and complex UK company structures as a front for illicit operations.

Finally, Companies House now have greater powers to share information, helping to cross check data with other public and private-sector bodies—including proactively sharing information with law enforcement agencies when there is evidence of suspicious activity or anomalous filings.

What does this mean for financial crime and compliance programs?

The changes to Companies House will result in more accurate and complete register information. Therefore, organisations can rely on it for KYC and other verification and validation checks. With Companies House having the power to be a proactive information gatekeeper, organisations using the data can make better business decisions and quickly identify discrepancies between data provided during onboarding or remediations and data provided on the company’s register.

Limited Partnership Reform

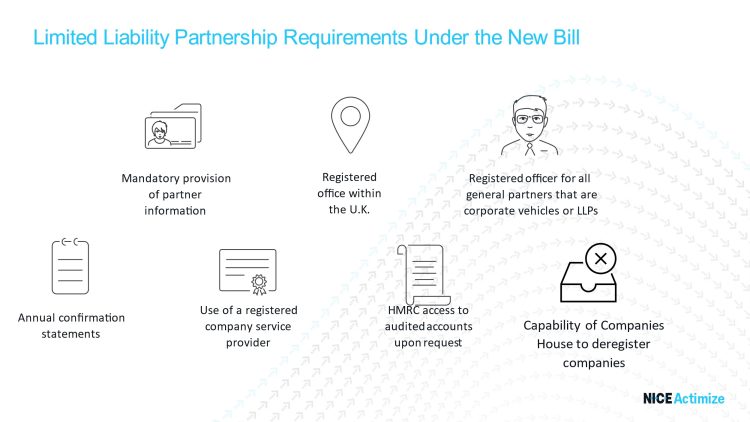

Another area targeted by the legislation is the reform of limited liability partnerships (LLPs.) The goal of the LLP reform is to make it harder for criminals to exploit the structure of limited partnerships for illicit purposes.

The reform includes the following changes:

- Provision of partner information becomes mandatory. Information includes personal details like name, date of birth, nationality, any former names and residential address. General partners will also need to provide a service address. For a partner that is a legal entity, the information required includes their registered or principal office address and a service address. A general partner who fails to notify the Registrar of partnership changes within 14 days will commit an offence and be liable to a conviction, which could result in a fine.

- Limited partnerships must always have a registered office within the UK, as opposed to the current model where the office can be based anywhere in the world. The Registrar for Companies will have the power to change the registered office of a UK limited partnership if it deems that the given address is not an appropriate address as defined by the Act.

- If a general partner is a corporate vehicle or Limited Liability Partnership (LLP), it must have at least one individual appointed as a registered officer. This registered officer cannot be a disqualified director and the Registrar must be able to contact this person.

- Limited partnerships must file annual confirmation statements, ensuring accurate and up-to-date information is reported to Companies House. This brings LLPs’ requirements in line with those adopted for UK limited companies (LLCs). LLPs must file their annual confirmation statements within 14 days of when the annual report is due.

- Registration applications, as well as annual confirmation statements, must be made by a registered company service provider that is supervised under the UK’s AML rules. This increases the accountability and oversight of LLPs in the UK.

- New powers enable His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) to access partnership accounts upon providing written notice to the LLP. This would require general partners to prepare audited accounts for review by HMRC.

- New powers for Companies House enable it to deregister LLPs that have been dissolved or no longer conducting business. They can enact this power when the LLP has not provided any notice of dissolution and Companies House has reasonable cause to believe the LLP is no longer operating, for example, when they cannot reach the LLP.

What does this mean for financial crime and compliance programs?

To manage your organisation’s risk, you will need to ensure that any LLPs on your books are compliant with the new legislation checking that:

- They have a UK registered office

- There is at least one individual appointed as a registered officer

- They are filing annual confirmation statements

Make sure your customer’s KYC record is updated with this new information. It’s not an organisation’s responsibility to enforce these requirements, but any LLP customer who fails to conform to the new legislation should become a high-risk customer. At that time, questions to ask would be about why the LLP is failing, and what steps they are taking, if any, to meet the new legislation. If an LLP is unwilling to conform to regulations, it could be because it’s a criminal entity which, up until that time, was exploiting the existing LLP structure loopholes.

Organisations should also monitor LLP transactions to identify any suspicious transactions, which could suggest an LLP is still maintaining a suspicious or complex offshore structure.

Failure to Prevent Fraud

The introduction of this new offence is significant: it’s designed to target organisations with inadequate antifraud prevention procedures that are financially benefiting from fraud committed by their employees or agents. Examples of this type of organisation could be unscrupulous sales practices or dishonest processes such as falsifying or hiding information needed by victims to make an informed decision.

The employees or agents must have committed a fraud offence (under the Fraud Act 2006), for an organisation to be liable for the failure to prevent it. However, executive awareness of the fraud offence is not necessary. The company bosses do not need to have ordered or even known about the fraud committed by employees or agents.

The offence is exterritorial jurisdiction, meaning if the organisation targets UK victims, even if the company or the employee is based overseas, they can still be prosecuted under this legislation.

What does this mean for financial crime and compliance programs?

This means that an organisation is responsible for ensuring they have the appropriate controls in place to monitor employees and any agents operating on behalf of the company and prevent them from committing fraud or engaging in fraudulent behaviour.

Companies must demonstrate that there are appropriate antifraud controls in place, and they continually monitor these controls to ensure they are adequate and fit for purpose. Not only should there be appropriate controls, but companies also need to have the right systems in place to monitor and alert on suspected fraudulent behaviour by employees.

Impact of New Legislation

The impact of the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act in fighting financial crime cannot be overstated. It represents a new era in legislative response and is a testament to the ongoing commitment of authorities to fight financial crime and protect the integrity of the financial system.

By strengthening data sharing between the public and private sectors, tightening regulations on company registrations, adding robust reforms for limited partnerships, and including an offence of failing to prevent fraud, this legislation represents a significant step forward in the fight against money laundering and other financial crimes. The Act’s success, however, ultimately depends on its effective implementation and the collaboration of all parties involved. As other countries take note of the UK’s progress, the hope is that pioneering legislation like this will inspire similar action worldwide, paving the way for a truly global effort to combat financial crime.

Technology can help organisations maximise the benefit of these changes in their risk and compliance programs. Your firm can use technology to aid in information sharing, whether it’s to share new detection models and typologies or suspicious activity information, or to automatically update customer records with the latest corporate or LLP information from Companies House. Technology can ensure your firm is maximising the value of the richer corporate registry information to identify, manage and mitigate customer risk.

For more information on how NICE Actimize can help your organization navigate the new legislation with technology solutions, go here.