Outpace First-Party Fraud and Mule Activity

February 28th, 2024

First-party fraud is when the fraudster doubles as a customer. Fraudsters will open accounts for the specific purpose of executing their fraud schemes. One common example these days are money mules who open accounts for fraudsters, enabling them to transfer money through multiple banks and countries to avoid scrutiny. In this blog, we cover how to stop losses to first-party and money mule fraud, along with how to move away from a narrow definition of third-party fraud loss on the profit and loss account (P&L) to a wider definition as per the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Fraud Classifier.

First-Party Fraud vs. Mule Activity

First-party fraud (FPF) happens when a person who applied for an account starts the fraud or abuse, rather than a fraudster making a payment away from a genuine customer’s account. FPF can start at the application stage or at any point in the customer life cycle.

Common FPF forms include:

- Checking account abuse on a current or deposit account

- Bust out, where a fraudster obtains facilities, gets a credit card or completes a loan, then disappears without paying

- Check kiting, where fraudsters cross-deposit checks of increasing values at different financial institutions

- Making false claims of fraud

- Engaging Money Mules to move funds

Fraud types overlap in this space: They might have different underpinnings but similar outcomes. At the new account stage, this includes:

- Identity theft, which covers stealing and using a real person’s identity and information

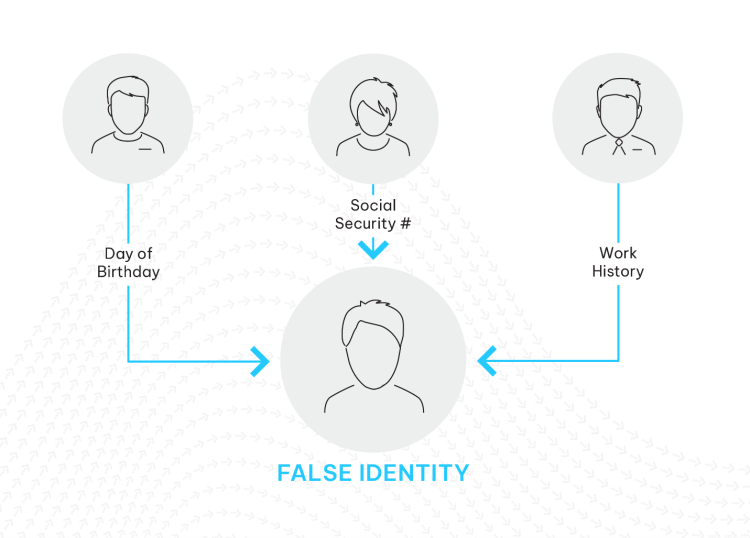

- Synthetic identity, where fraudsters use real and fake information to create a new identity that’s used to perpetrate fraud

Identity fraud is a third-party type, but it will appear like FPF until the genuine customer disputes it.

Fraudulent Misrepresentation

Fraudulent misrepresentation is when a genuine person is applying, but they lie about personal details, such as address history, or income and expenditure, to hide bad debts or get accounts or facilities they would not otherwise be granted. It’s possible that they intend to use the account or facility genuinely, but the bad rate on these transactions will be higher. In any of these categories, the fraudster might be planning to undertake, bust out or commit mule activity or abuse.

False claims on cards continue to rise, whether disputes or fraud, in part due to professional refunders who are paid fees to obtain an item, such as a new computer, for free. Fraudsters are well aware of the tricks professional refunders use to ensure that something is ‘refunded’ by the retailer, such as claiming non-delivery. They are well-versed in the merchant’s rules and work in tandem with a customer to secure a refund. Assuming 3-D Secure wasn’t used, the liability is with the merchant, not the issuer.

Money Mules Angle

Money mules are a type of FPF that is difficult to detect. The account may have been opened genuinely and then sold on or become involved as a mule account later. Some money mules can be witting or unwitting: a witting money mule may have fallen for an employment scam. An unwitting money mule might not even realize the account is compromised.

Economic recession tends to correlate to increased fraud, so if people fall on hard times, they’re more vulnerable to fraudsters recruiting them as money mules. In past recessions, we’ve seen a correlation with increased fraud, and it’s likely this downturn will be the same. As people come under pressure, they may do things they would ordinarily not do, as they often find it easier to rationalize illegal actions.

First-party Fraud and Bad Debt

Hidden fraud increases costs overall and tends to hit banks’ bad debt line, rather than appear on the fraud refund line. But it’s the size of these losses and their impact on profitability that are key, and where these illicit funds go to from a regulatory perspective.

Surprisingly, some firms say they don’t have an FPF problem. Then they wonder why their bad debt is so high and rising. In a portfolio with no FPF definition, fraud can be in excess of 25 percent of the bad debt and even higher, because outdated controls don’t reflect the real causes.

Combat First-Party Fraud and Mules

The U.S. Federal Reserve’s Fraud Classifier breaks out first-party fraud, and measuring first-party fraud is the first step into managing it better. The best approach is to use the data you have to create a model to categorize elements of your bad debt as fraud. Though fraud is only confirmed through investigation, this information loaded in databases is a good tactic for internal monitoring purposes.

Examples of data to include in a model:

- Early defaults, such as three payments down in the first six months

- High excesses, such as 50 percent over limit

- Loan churn prior to default

- Bust out indicators

- Internal and external data matches that show a high risk of fraud

When reviewing cases to confirm fraud, look for:

- Fake documents

- Clear misrepresentation, including hidden address with adverse credit data

- Inability to contact the account holder

- Claim of ID theft by a genuine party

Use this model to build both new account and ongoing behavioural analytics models and rule sets.

At account opening, it’s prudent to bring in improved identity and verification data, as well as multiple models for risk scoring. This doesn’t just look at credit worthiness—it can identify the account holder as a fraudster or money mule. Data should include velocity of applications from the same IP addresses, devices, phone numbers, and postal and email addresses.

With money mules, accounts might still be opened due to insufficient reason to decline. Placing visible or invisible restrictions on these accounts that are updated throughout the customer life cycle can speed up identifying money mules.

To help detect and reduce FPF, build out specific strategies and processes. Create challenge processes in your cards teams based on models to detect potential fraudulent behaviour. This evidence can help your team change a customer’s mind by making it clear to them that they could be committing fraud.

Consider having separate collections strategies for fraud, which can then also feed into the FPF models. Taking these steps will help you avoid wasting resources on collections where there’s no chance of getting the money back.

Share KYC and CDD data between areas so it can be used in fraud management systems. This can be used at account opening and ongoing so that changes in behavior, such as sudden increases in turnover compared to the application or more recent history. It’s a good way to expose mules by using existing outbound payment systems to stop money from leaving the bank, while ensuring case management tools are used to have separate processes for FPF.

Cost of Fraud

Measuring fraud is only the beginning: it’s important to understand the full costs, too. This includes cost of:

- Opening accounts

- Checks involved

- Running accounts and the net present value (NPV)

In addition to these costs, add bad debt rates for the account types.

Develop a roadmap to move to an enterprise fraud management system so you can take a multilayered approach and properly share data. This will remove silos, enabling efficient case management. In addition, look to reuse technology investments from digital account opening throughout the customers life cycle for proper risk management. By taking a multilayered approach, FPF is uncovered, and technology investments can be directed to making banking even more safe and profitable.

Visit our Enterprise Fraud Management Solutions webpage to read more about the different solutions NICE Actimize has to offer.